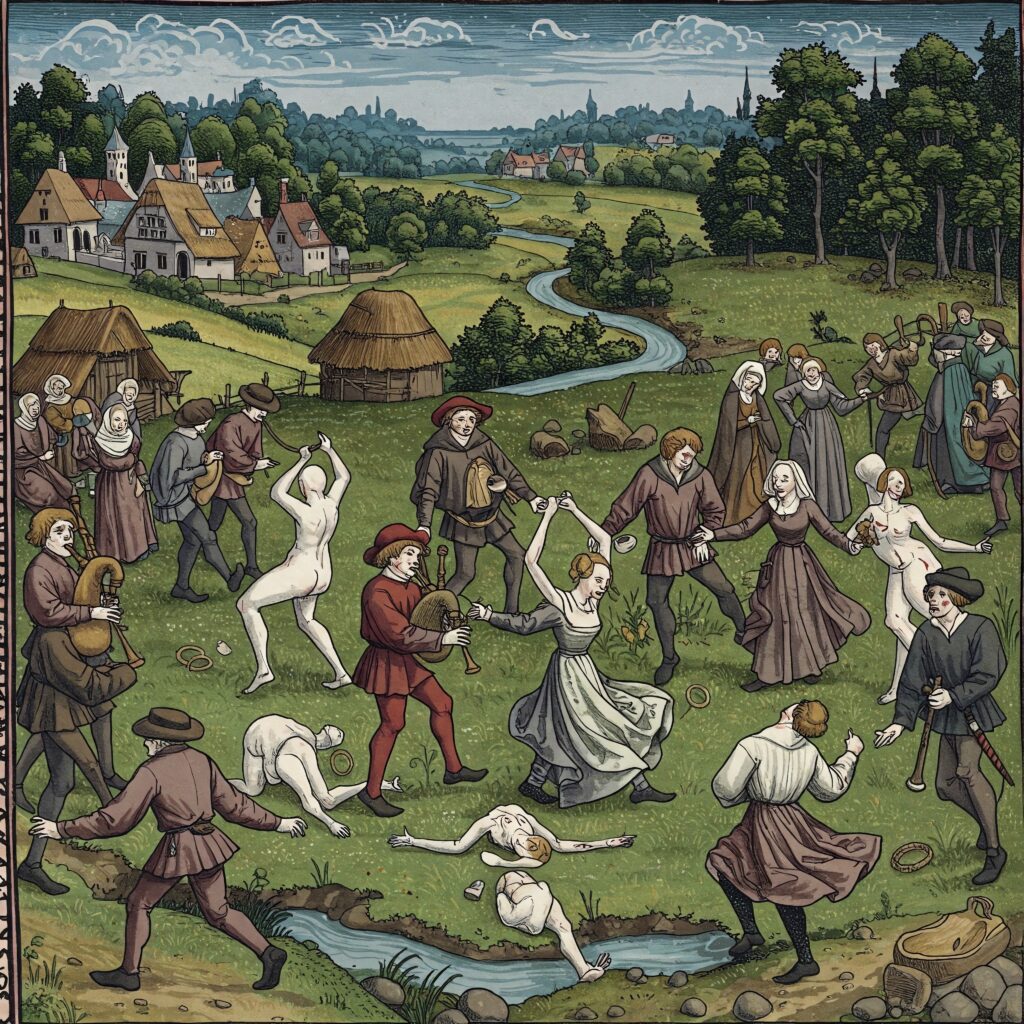

During summer 1518 numerous residents of Strasbourg experienced uncontrollable dancing which produced an alarming situation throughout the city streets. A single woman began dancing uncontrollably which eventually spread to hundreds until some performers dropped from exhaustion until they died. These participants seemed different from usual festive revellers since their bodies moved involuntarily. During this period when scientists lacked sufficient understanding of phenomena the population explained the events as supernatural divine retribution or devilish possession. Modern science provides a rational explanation regarding the biological factors which triggered this large-scale compulsive movement outbreak.

Mass Hysteria: How Stress Can Rewire the Brain

The scientific community now understands the Dancing Plague as an example of mass psychogenic illness which scientists also label as mass hysteria. When people gather under conditions of high stress, they develop identical physical symptoms that doctors cannot explain even though no medical condition exists. The people of Strasbourg experienced famine together with disease and economic instability during a period suitable for psychological outbreaks. People in stressful environments who observe abnormal behaviors trigger their mirror neuron system to mimic social actions and this increases the likelihood of behavioral spread. The mechanism behind such psychological propagation remains clear by demonstrating how one performer could spread the effect without being aware. Basically, it was just like a 16th century’s viral TikTok trend- but instead of learning the dance, you were possessed by it.

Neurobiology and the Role of the Basal Ganglia

The Dancing Plague displayed neurological signs of movement disorder because the basal ganglia brain region failed to control voluntary movements. Scientists postulate that those affected by the plague exhibited symptoms of chorea which manifests through involuntary jerky movements because of infections including Sydenham’s chorea triggered by streptococcal bacteria. The poor sanitary conditions and numerous diseases in medieval Europe could have resulted in an unidentified neurological condition that contributed to the outbreak.

Instead of using rest or quarantine measures, the city rulers chose a different method to treat the dancers to stop dance uncontrollably… by making them dance more. The rulers of Strasbourg hired musicians to perform in public streets which transformed the entire outbreak into a historic yet disastrous mass dancing event. Seeing a guy drowning and thinking the best solution to save him is throwing more water is kinda (!) resembles this situation.

The Ergot Poisoning Hypothesis: Hallucinations and Convulsions

Another compelling theory which is ergot poisoning happens when people consume bread infected with Claviceps purpurea fungus which grows on rye. This toxic mold causes the poisoning effect. Ergot alkaloids function similarly to LSD products when they enter the body thus causing hallucinations as well as muscle spasms and convulsions. St. Anthony’s Fire symptoms match precisely with the wild unregulated movements experienced during the Dancing Plague. The critics of ergot poisoning propose that this toxin leads to paralysis and not to the sustained coordinated movements of dancing that occurred during the pandemic. The unusual mental state which ergot possibly created led people to become more susceptible to mass hysteria even though it did not exclusively cause the phenomenon. Imagine getting a microdose of medieval LSD by simply craving a sandwich- harsh times.

Music, Rhythms, and the Brain’s Response to Repetitive Movement

Another significant part of the Dancing Plague emerged from its connection to music. The local authorities attempted to control the disorder by using musicians, but their actions unexpectedly expanded the outbreak. Synchronous sound patterns in the brain produce significant neurological changes leading to states resembling trance. That repetitive beat research into brainwave entrainment shows that these sets in turn affect mental processes causing dissociative states. Thus, we can explain why presence of musical sounds did not lead to decreased compulsion among the dancers but rather increased their compulsive behavior.

Could a Modern Dancing Plague Happen Again?

Modern society experiences naturally occurring mass psychogenic illness despite the low probability of massive compulsive dancing outbreaks today. Modern-day collective behavioral anomalies affecting human psychology emerged again in the 1960s with the Tanganyika Laughter Epidemic followed by the Pokémon Seizure Incident in 1997 and the recent “TikTok Tics” outbreak among teenage populations during the 2020s. The fast pervasive nature of mass hysteria through social media channels becomes a new pathway for symptoms and behavior spread rapidly. The 1518 Dancing Plague remains a powerful demonstration of how basic human factors interact unpredictably with psychological along with neurological elements and natural environmental elements.

Today people get consumed by viral trends combined with misinformation and digital mass hysteria rather than the former ‘street dancing wave’. The important question concerns how historical events will be repeated and not whether they will repeat.

Therefore, the next time we find experience a frenzy, whether it be online or offline, we should pause for a second (if our brain let’s us) and ask ourselves: Are we moving to the rhythm or just simply following the crowd?

We got inspired by those articles to create this content

My name is Meliha Çay, and I am currently a 3rd-year Bioengineering student at Marmara University. Writing has always been a passion of mine, and now I have the incredible opportunity to combine it with my academic field as the Content Manager for Biologyto. My mission is to make science accessible, fun, and engaging for everyone. At Biologyto, we aim to inspire a love for science through articles that are not only informative but also full of excitement and creativity. I hope to spark curiosity in others and help them explore the amazing world of bioengineering and beyond.